Institutions not only structure any sort of social interaction[1], but are also essential in solving societal problems[2], such as climate change and the associated threat towards a fair and just future. It is not without reason that the United Nations particularly emphasized institutional progress within SDG 16[3] to advance to a more effective, inclusive, and accountable society. In a recent study, it was found that institutions matter to a great extent when scrutinizing the relationship between corporate financial performance (CFP) and ESG performance. More specifically, the institutional environment a company finds itself in determines whether sustainable business practices get transformed into financial returns.

The claim that more sustainable companies are outperforming their not so sustainable peers is not new[4] and the consequent shift of investors’ preferences towards more sustainable companies has been taking place with increasing speed over the last decade[5]. Associated wake-up calls and the urge to take ESG into consideration are not surprising either. Besides the alleged desire of investors for a just and sustainable future, this shift is more likely based on the theory that sustainable finance delivers abnormal returns[6]. But is the relationship between sustainable behavior and financial performance as straightforward as it is disseminated? Are more sustainable corporations indeed more likely to achieve better financial results regardless of where they are and what they do?

In fact, when utilizing ESG scores, rankings, and performance as a proxy for sustainable behavior, two meta-analyses[7] [8] concluded that in most empirical studies the resulting relationship was not as simplistic, universal or linear as it is often propagated. In a corresponding literature review, the researchers also identified a large number of discrepancies among scholars in how to statistically model the relationship, what control variables to use and how to even quantify the dependent and independent variables of focus. Following these insights, the researchers uncovered a determining factor in establishing and shaping the emphasized relationship – institutional quality.

Key Findings

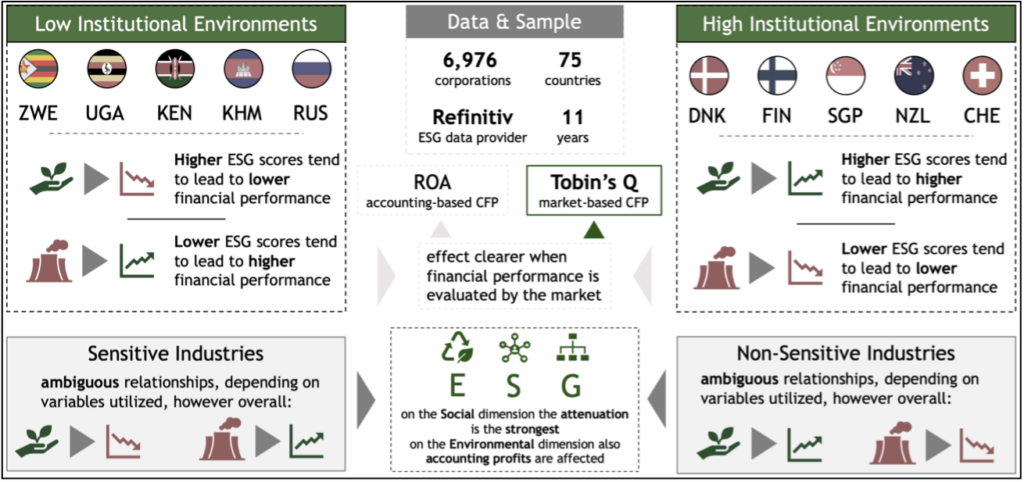

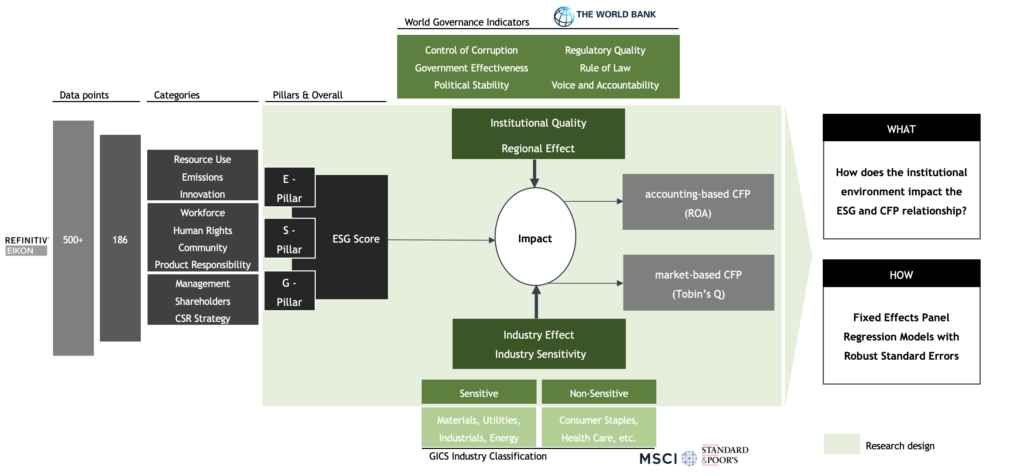

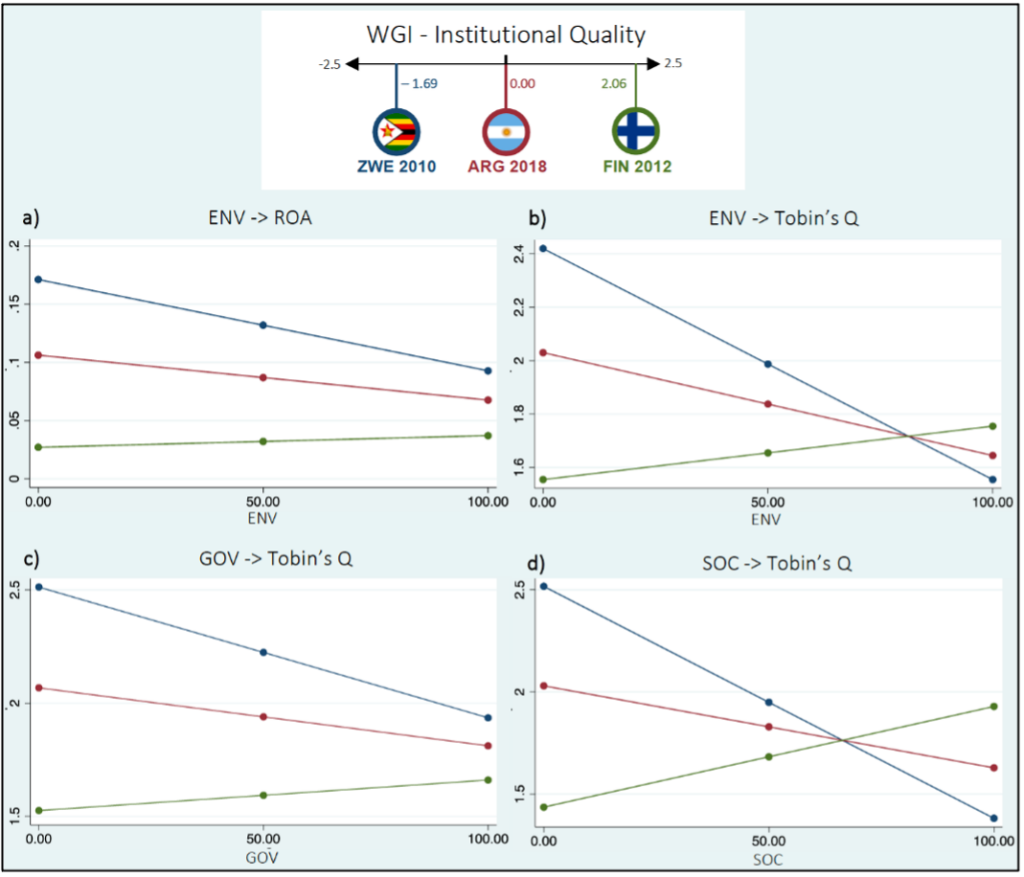

The final sample consisted of datapoints from 6,976 corporations, situated in 75 different countries over a period of eleven years or, specifically, from 2009 to 2020. Subsequently, these were analyzed applying fixed effects panel regression models. Both an accounting- and a market-based measure were used to quantify corporate financial performance, respectively, Return on Assets (ROA) and Tobin’s Q. Meanwhile, ESG performance was proxied by ESG scores from Refinitiv (former Thomson Reuters). The variables associated with institutional environment were split into

- Institutional Quality, calculated through a factor analysis and based on the World Governance Indicators from the World Bank and

- Industry Sensitivity, a dummy variable equal to 1 if the GICS industry of a firm was deemed sensitive towards ESG.

Institutions Are Among The Determinatal Factors For The Link

Interestingly, the general statistical analysis of ESG and CFP did not yield any significant results, however, when moderating effects stemming from the institutional environment were introduced, this changed. Under high institutional quality, the researchers found a positive relationship between ESG scores and financial performance. Contrarily, the relationship was negative under low institutional quality. Exemplified below by the case of Finland 2012, Argentina 2018 and Zimbabwe 2012, institutions can be seen as the determining factor for direction of the focal link. Furthermore, the industrial environment a corporation finds itself in was found to affect the relationship ambiguously. Generally, sensitive firms seem to receive relatively less financial gain for improved ESG performance, and it may even be negative.

Possible Explanations for Such Dynamics

- Legal institutions, such as environmental regulations, labor laws or health and safety requirements, can serve as the means of reflecting sustainable behavior inside a company’s balance sheet. Finland was for instance the first country to introduce a carbon tax capturing corporate pollution by giving it a price and hence affecting accounting profits.

- In highly corruptive settings, where the trust of the general public is lacking, the likelihood of sustainable activities being perceived as greenwashing and thus not rewarded by investors, could be another reason for an inverse relationship in low institutionally developed regions.

- In line with the previous, when accountability is low, and corporate entities can disclose information without third party verification, it could be relatively easy to stay focused on short-term profits through unsustainable practices but still receive a better ESG rating.

- In environments with low institutional quality, banks tend to only give out short-term loans in order to reduce their own risks. This can lead to a vicious cycle of corporate lenders also only focusing on short-term profit maximization which then again decreases their access to capital, constraining their ability to engage in long-term sustainable practices.

Putting The So What Into Practice

When setting out for systemic change, it is important to ensure the necessary institutional environment in order to encourage individuals, as well as corporate entities to act in the best interest of the entire society and the planet. Thereby, a bottom-up approach focusing on incentivizing every individual and a top-down approach, fostering legal macro-level change can be synthesized, leading to the best possible outcome. These institutions should seek to maximize accountability, transparency, and mechanisms to internalize negative externalities. Corporations within such environments should fully leverage opportunities associated with sustainable practices, such as cheaper access to capital, in order to incrementally advance the progress towards a just space for humankind. Corporations, which are especially sensitive towards ESG related elements irrespective of their ESG scores, should aspire to enhance their own credibility, as this might award them with a competitive advantage. Lastly, societies with high institutional quality should strive for teaching about their institutions and the associated benefits to everyone else, as a global problem can only be solved on a global level.

References

Doppler, A.R., & Elboth, L.B. (2022). Institutional Quality, Industry Sensitivity and ESG: An Empirical Study of the Moderating Effects onto the Relationship between ESG Performance and Corporate Financial Performance (Unpublished master’s thesis). 22098. Copenhagen Business School, Denmark.

Lisa Bernt Elboth recently graduated with an M.Sc. in Applied Economics and Finance as well as a CEMS Master’s in International Management from Copenhagen Business School and Bocconi University. Her interest in global matters and sustainability has flourished during her studies impacting the choice of master thesis topic and this subsequent blog contribution.

Adrian Rudolf Doppler works as a research assistant for the Department of International Economics, Government and Business at Copenhagen Business School and had just graduated with a Master’s in Applied Economics & Finance and the CEMS Master’s in International Management after a two-year journey. He had always been passionate about ESG, Sustainability and the existing links with the capital markets, as well as the complex system dynamics arising form it.

Kristjan Jespersen is an Associate Professor at the Copenhagen Business School. He studies on the growing development and management of Ecosystem Services in developing countries. Within the field, Kristjan focuses his attention on the institutional legitimacy of such initiatives and the overall compensation tools used to ensure compliance.