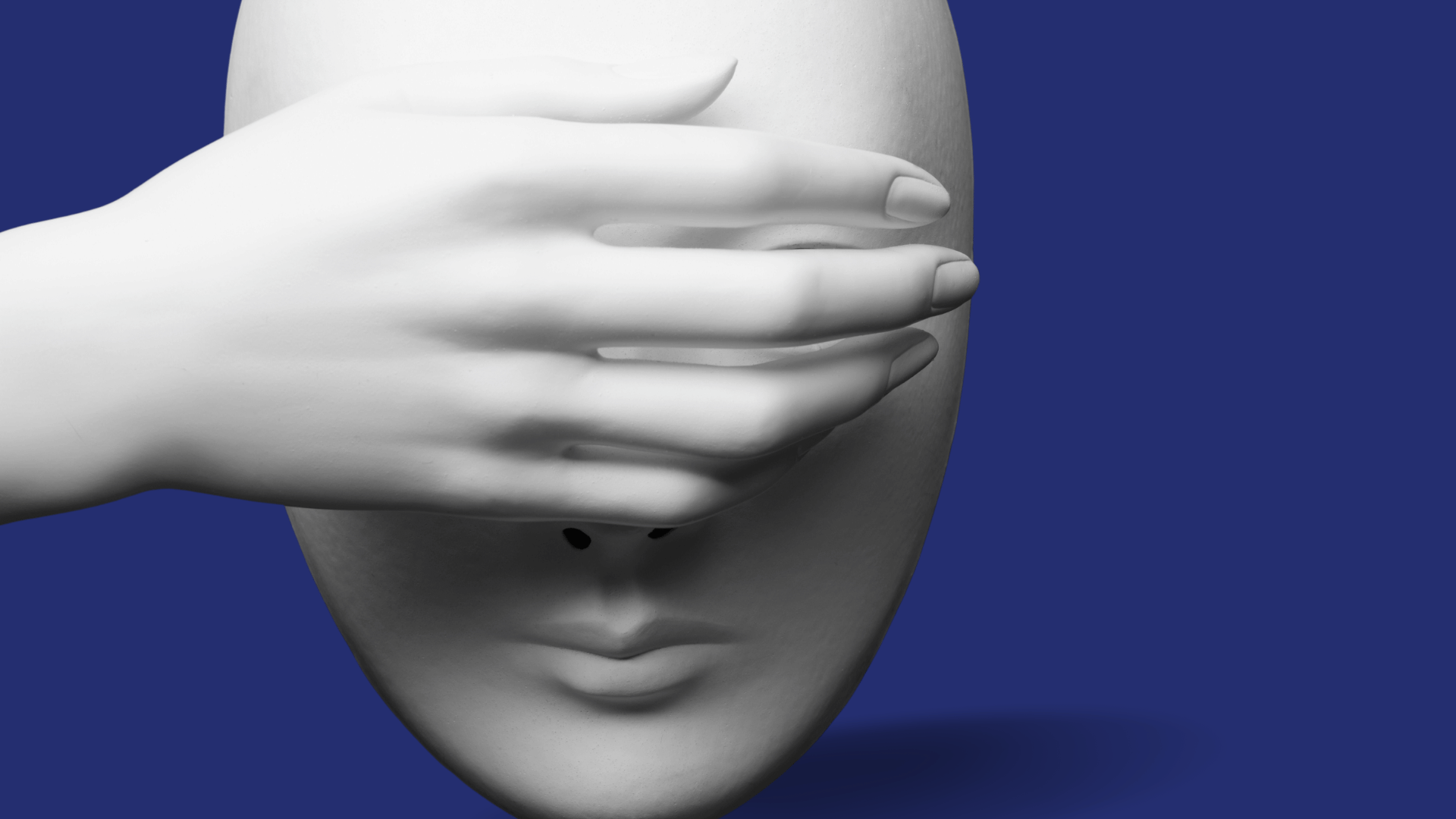

Corporate sustainability (and related concepts like ESG and materiality) have been reduced to discussions around financial value. This makes these concepts “ethically blind”. We are in need of a resurgence of business ethics, otherwise the endless discussions of the “business case” for sustainability will turn out to be the error at the heart of true leadership for sustainable business practices.

My LinkedIn and Facebook feeds are filled with great stories about how well corporate sustainability aligns with financial measures (be it revenue, profit or another metric). Sustainability practitioners seem to love these research findings. No one can blame them. They are the ones who need to “sell” sustainability efforts to top management, and having evidence that sustainability aligns well with financial goals makes this task a lot easier. I do not necessarily doubt these findings, although any researcher will tell you that results always depend on how a study is built, and also that correlation and causation are often confused in these studies.

What I am concerned about is that research findings are turned into normative prescriptions without much reflection: just because some research finds that corporate sustainability efforts support the financial bottom line of a company, we should not conclude that these efforts should only be undertaken whenever they support the financial bottom line. Corporate sustainability is most urgently needed whenever it does not support the financial bottom line. In those situations, the decision for sustainability is a tough one; it requires courage and, in many cases, ethical reflection.

Future thinking, writing, and speaking about corporate sustainability needs to much better balance the financial gains and the moral dilemmas attached to relevant issues. Otherwise, we risk to become ethically blind. Such blindness is often referred to as the “inability of a decision maker to see the ethical dimension of a decision at stake.” (Palazzo et al., 2012: 325) Practitioners’ and academics’ obsessions with the business case has clearly diminished our ability to turn a problem/issue into a case for moral reflection and imagination.

A good example are materiality assessments. These assessments rank ESG issues according to their influence on a firm’s strategy (incl. financial bottom line) and the interest of the firm’s stakeholders in these issues. The moral need to address an issue, because it is the right thing to do, falls off the agenda. Corporate sustainability becomes a pick and choose exercise, which corporations often frame in whatever way they please.

The field, which we nowadays refer to as corporate sustainability (incl. ESG and materiality etc.), started out with discussions around the moral responsibility of businessmen. Back then the focus was, among other things, on how moral dilemmas can be resolved. I am not saying these are the good old times. But it is clear that the discourse has not only changed label (from ethics to responsibility to sustainability), but also that this very discourse has been hijacked by the belief that corporate sustainability is only a worthwhile endeavour whenever it creates financial value for a company.

All of this is not to say that corporations should not financially profit from their corporate sustainability efforts. It is also not to say that managerial tools like materiality assessment are completely useless – they can be of great help. However, it is to say that we cannot and should not reduce discussions around sustainability to a single dimension: be it the financial one, the moral one, or any other one. Corporate sustainability issues are by design multi-faceted, and so must be our thinking about them.

Former CEO of General Electric, Jack Welch, once famously declared:

On the face of it, shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world. Shareholder value is a result, not a strategy …your main constituencies are employees, your customers and your products” (quoted in Moon, 2014, p. 106)

We should extend this argument to the business case for sustainability. The idea of a business case itself is a stupid one; such a case should never be the sole motivation of engaging in corporate sustainability, although it can be an outcome of such engagement.

I prefer morally informed decisions. But it is getting harder to convince practitioners and academics that there is more to corporate sustainability than the financial bottom line. Having a business case for corporate sustainability should never be a precondition for addressing an issue or a problem. Otherwise, we move towards moral mediocrity…

Sources

Moon, J. (2014). Corporate Social Responsibility: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford et al.: Oxford University Press. Palazzo, G., Krings, F., & Hoffrage, U. (2012). Ethical Blindness. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(3), 323–338.

Andreas Rasche is Professor of Business in Society and Associate Dean for the Full-Time MBA Program at Copenhagen Business School. More at: www.arasche.com.